The Top 5 Most Common Mistakes in Landscape Photography

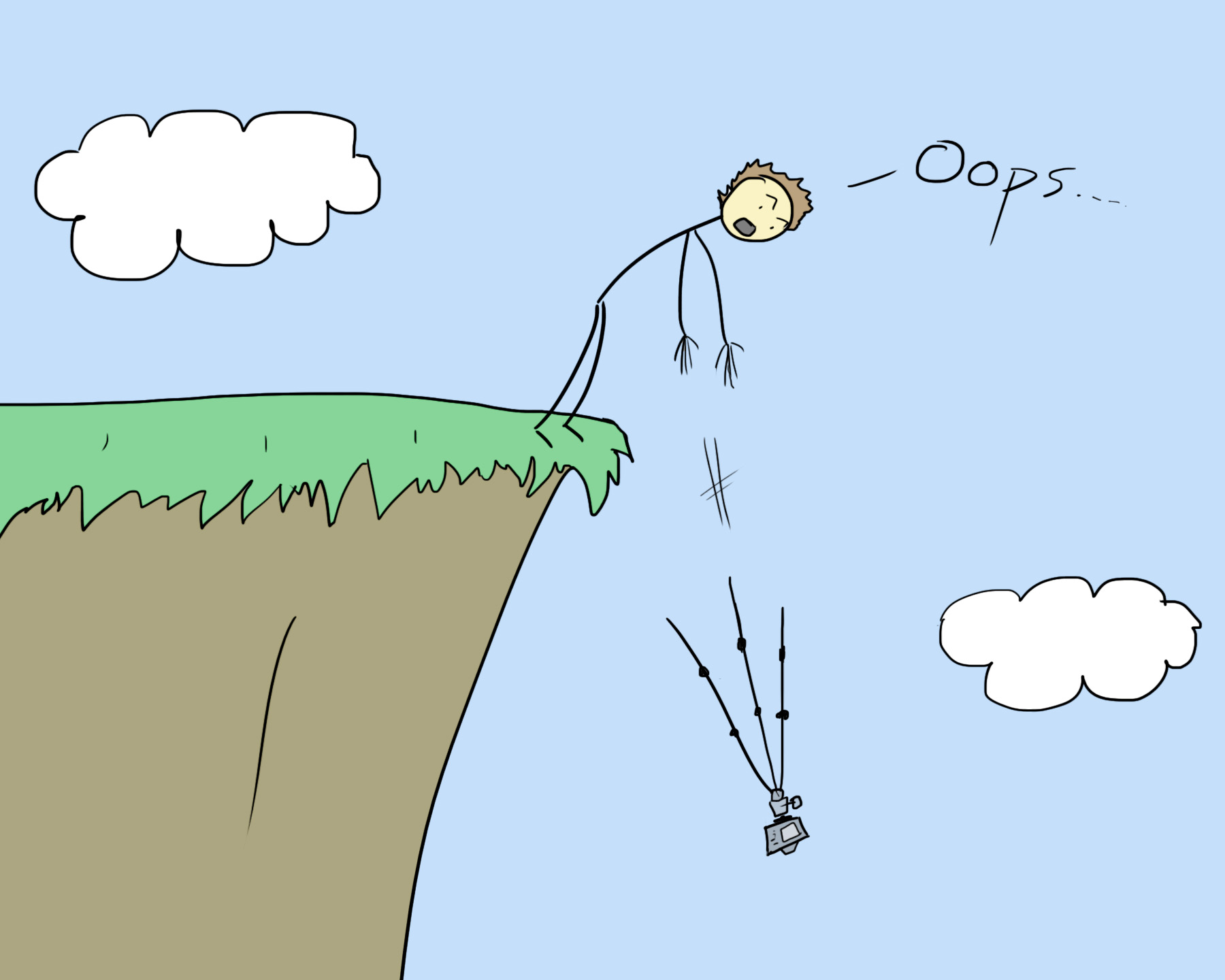

A user-friendly guide to understanding exposure in digital photography. If you’ve ever taken a statistics class you surely now have an innate phobia of histograms. But fear not, because this article is not a math pop quiz, and your camera’s histogram is not intended to give you cold sweats. Nay, it’s simply a tool to […]

In-depth Photoshop tutorials: https://www.joshuacripps.com/shop/video-tutorials/photoshop-basics-video-bundle/ https://www.joshuacripps.com/shop/video-tutorials/photoshop-advanced-video-bundle/ On-location Photography Workshops: http://www.seatosummitworkshops.com/ FB: https://www.facebook.com/JoshuaCrippsPhotography IG: http://instagram.com/joshuacrippsphotography Episode Transcript: When is white not white? When it’s blue, yellow, or orange. What the crap am I talking about? Even I don’t know! So stick around and we’ll both learn everything you need to know about White Balance. [opening credits] Hey […]

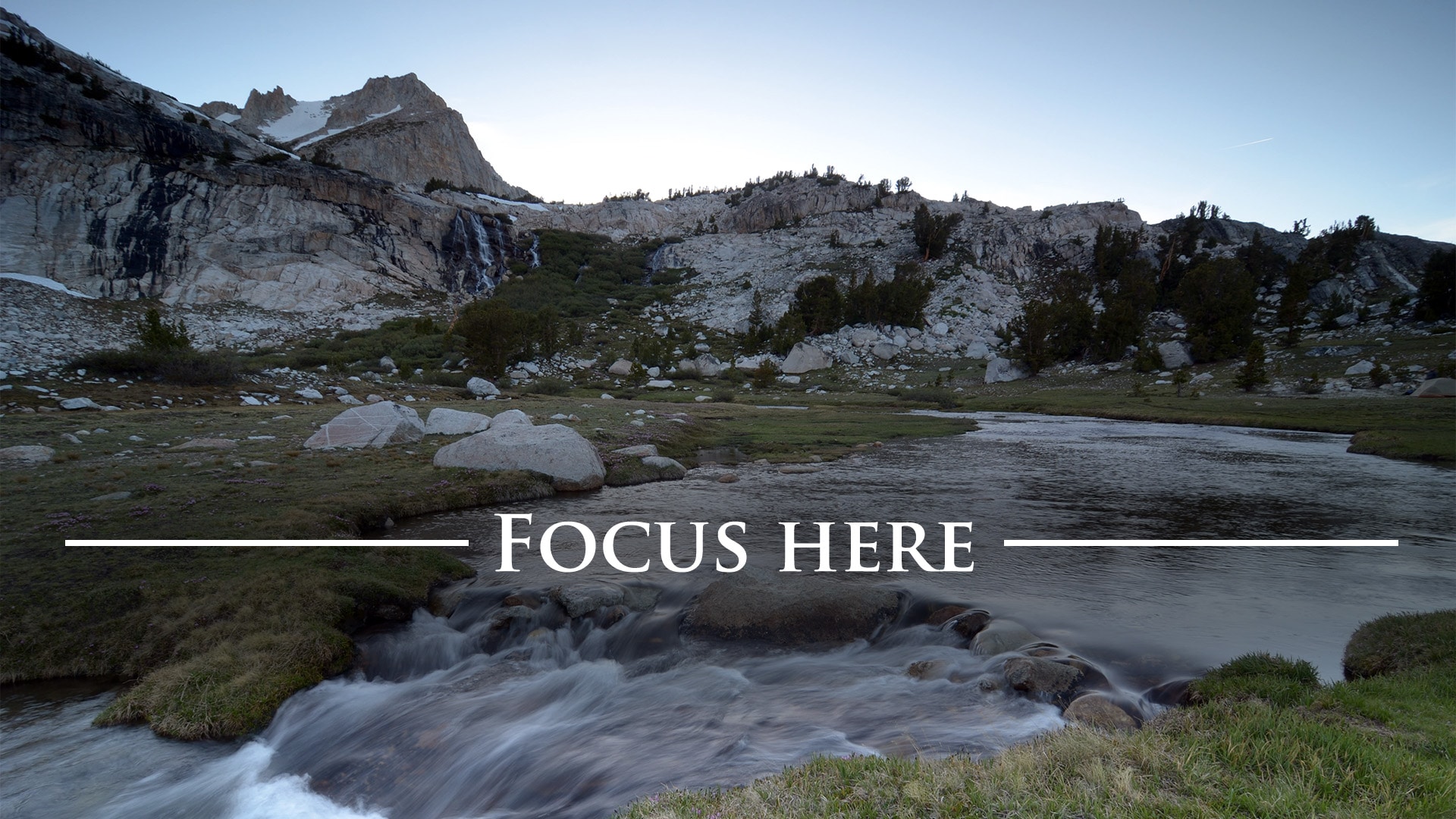

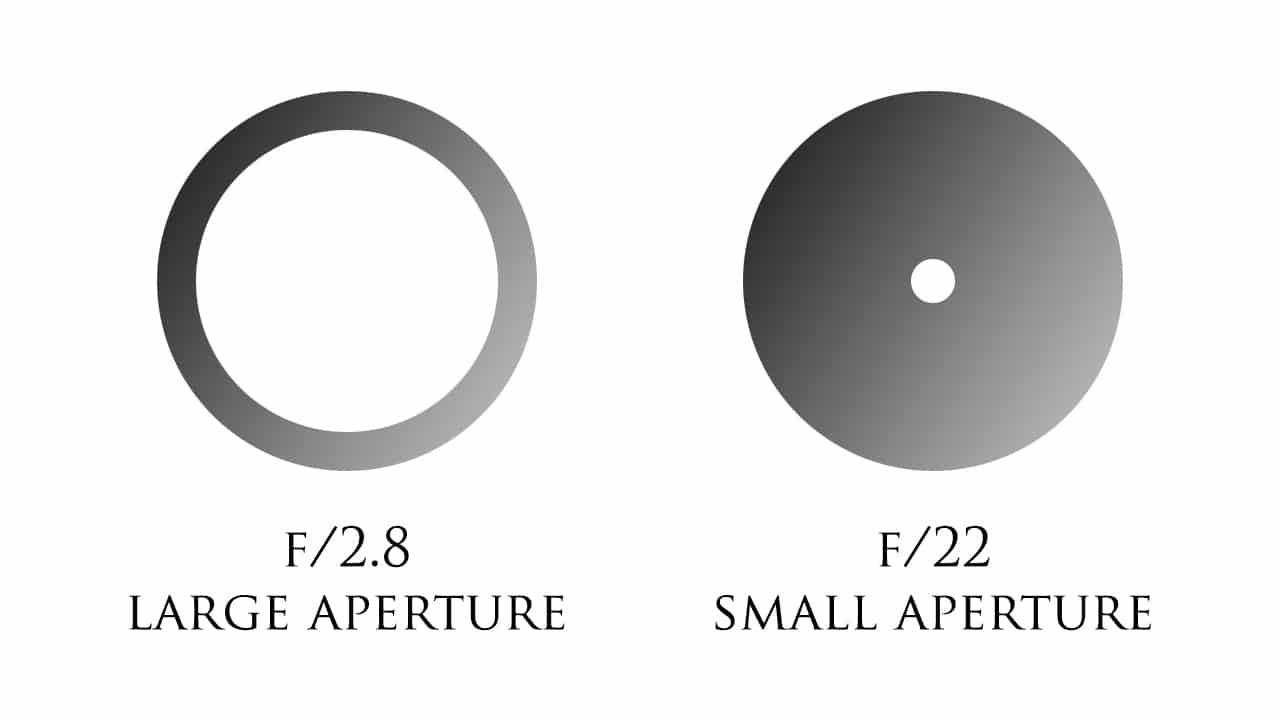

Episode Transcript: G’day, and welcome to Professional Photography Tips. Today we’re going to learn to be apturelutely awesome. Wait, what does that say? A-per-tu, Oh, aperture. Today we’re going to learn about aperture. [Puzzled look, snap]. [snap] There, that’s better. [opening credits] Hi everyone, Josh Cripps here. In our last video we learned all about […]

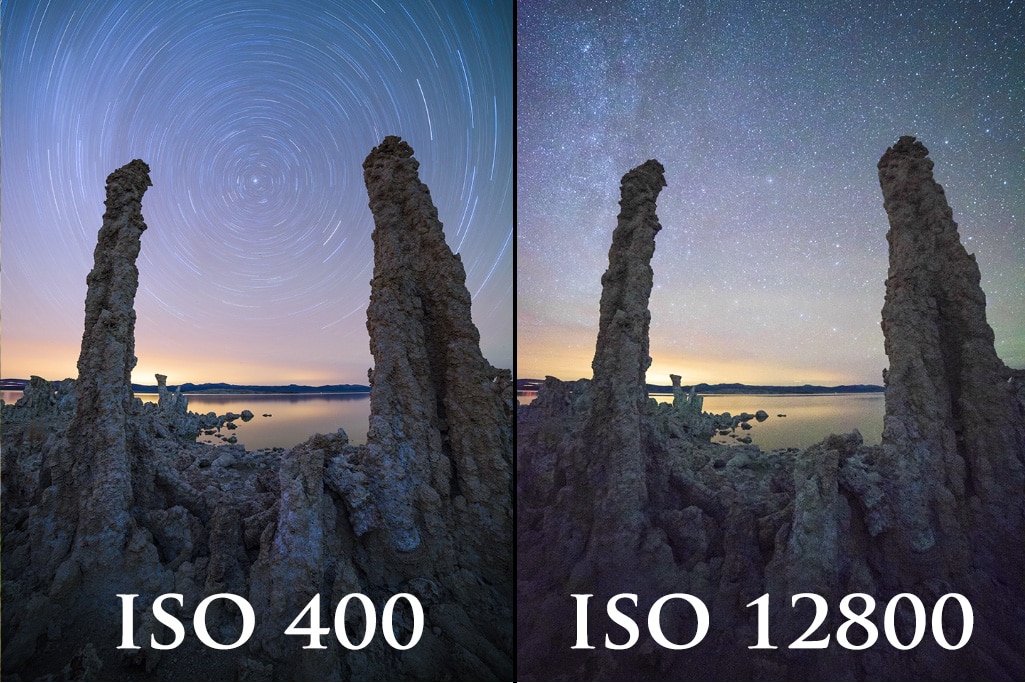

Episode Transcript: Want to become a master of time??? Then you need to understand shutter speed! [opening credits] Hi everybody and welcome to professional photography tips. I’m Josh Cripps and today we’re going to take an in-depth look at shutter speed. When most people think about a photo, they imagine some instantaneous, split-second thing happening. […]

Episode transcript: Confused by how aperture and shutter speed affect your exposure? Stick around and be demystified! [opening credits] Hey all, welcome to Professional Photography Tips. I’m Josh Cripps and here’s everything you need to understand about shutter speed, aperture, and exposure. Still confused? I don’t blame you, so let’s take a closer look. You […]

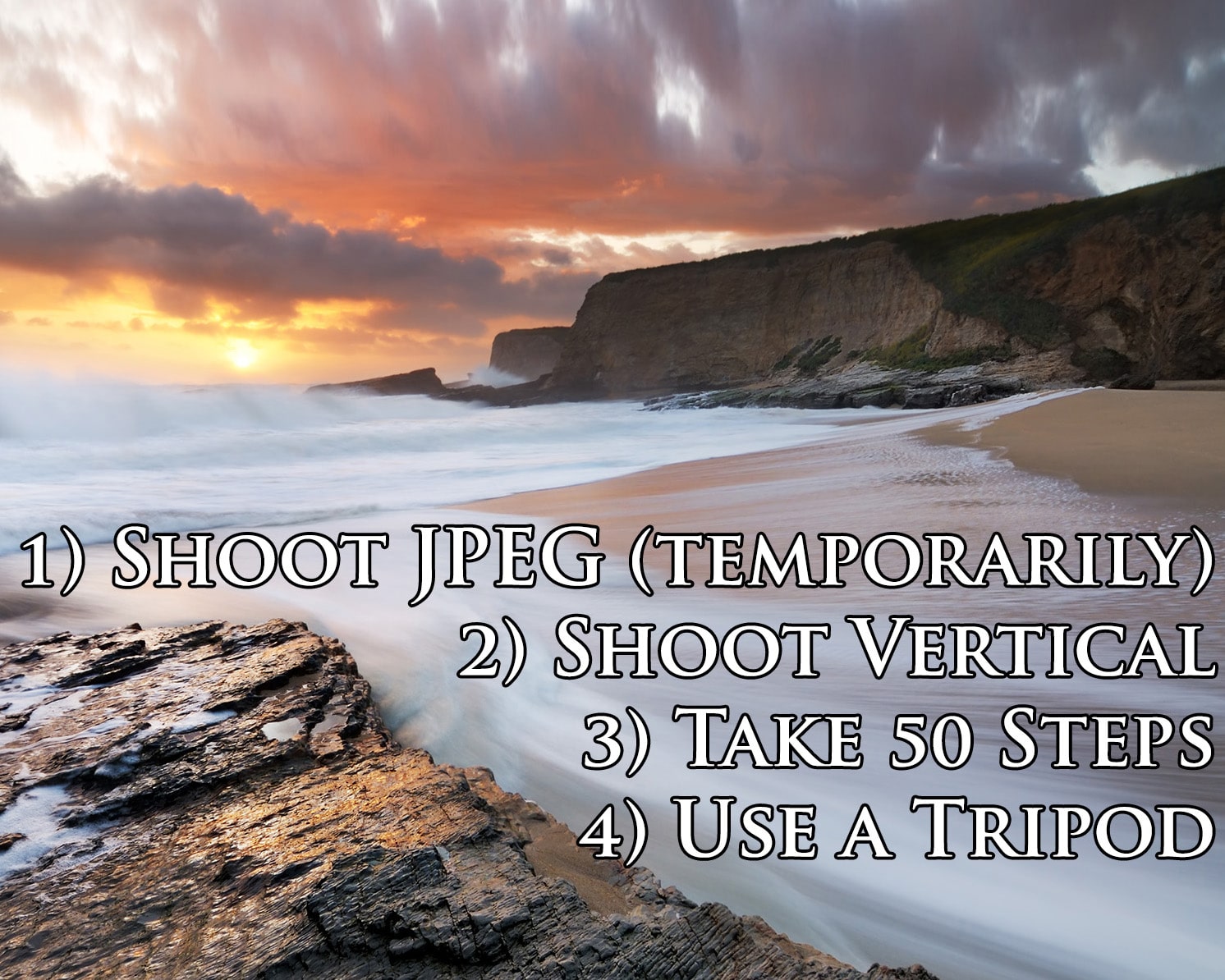

Episode transcript: Hi all, Josh Cripps here and I’m going to show you 4 things you can do RIGHT NOW to become a better photographer 1) Shoot jpeg only (for the next week) Ok, before you shut off the video hear me out. There’s so much you can do to a raw file in post […]