https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JtmjTm4yspQ&t=8s So over the last couple of months, throughout this whole coronavirus lockdown, I’ve gotten not a small amount of messages from people who have been feeling a little bit befuddled by this whole situation. They haven’t been feeling that inspiration, right? It’s really hard to want to get out and shoot when the government […]

A little history about myself: I don’t have any professional training or education in photography. I went to school for aerospace engineering and didn’t even pick up a serious camera until three years after I had my BS. Everything I know about photography I’ve learned through seven years of passionate practice, and lots of lessons […]

I have a huge problem: I’m constantly trying to save time. Everything I do I do as quickly and efficiently as possible. I’m an incorrigible list maker and when I’m on a roll I check off my tasks like a jackhammer: wham, bam, thank you ma’am. I have apps that save me time, gizmos that […]

I’m a positive guy, not normally prone to complaining. But today I have a bone to pick with all the photographers out there, myself included. It seems that while we continue to push the boundaries when it comes to capturing the world’s beauty in a visual way we’re sacrificing our ability to capture it in […]

Not everything is Epic, and that’s okay. Are we in such a rush to produce The Next Great Image that we forget that conditions aren’t always astounding? Lackluster sky? No problem, we say, I’ll just add a heaping helping of contrast in photoshop. Now it’s Epic! Forest colors aren’t quite as rich as we hoped? […]

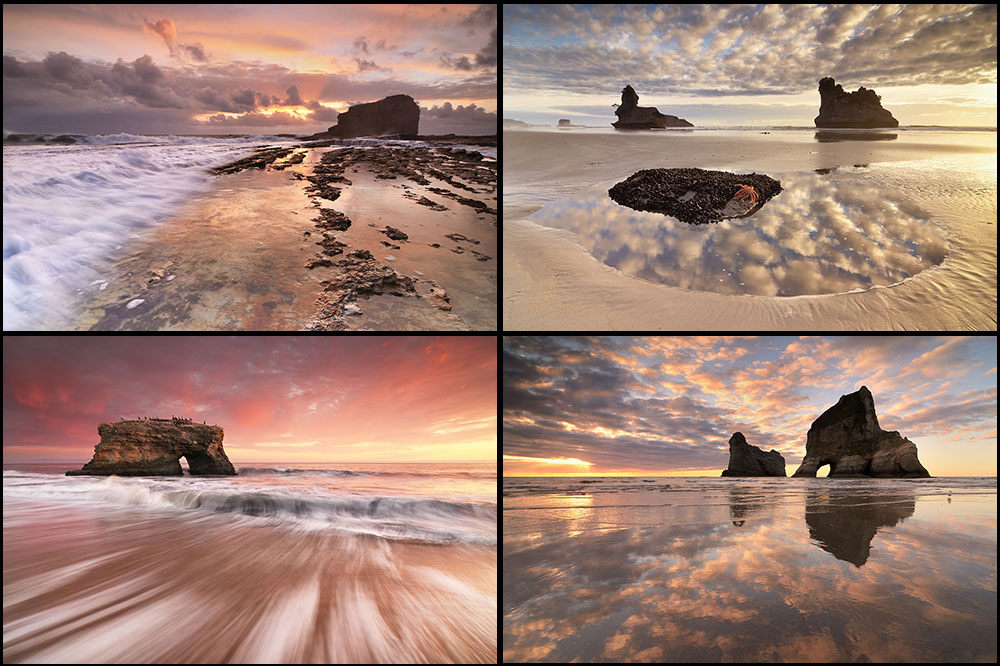

Is nature photography an art form? If you asked that question among the photographic community, I believe you’d get an unequivocal “YES!” as an answer. That nature photography is a form of art is something the I and many other photographers believe fully. But what if you asked that question among the general public? Or […]

Earlier today I showed a friend of mine my most recent photo, taken at sunset at a place called Abalone Cove. Now, my friend has been to this place before, and the first words out of his mouth were: “That’s not what it looks like.” In good fun, he also made some comments about me […]