That’s not what it looks like . . .

Joshua Cripps

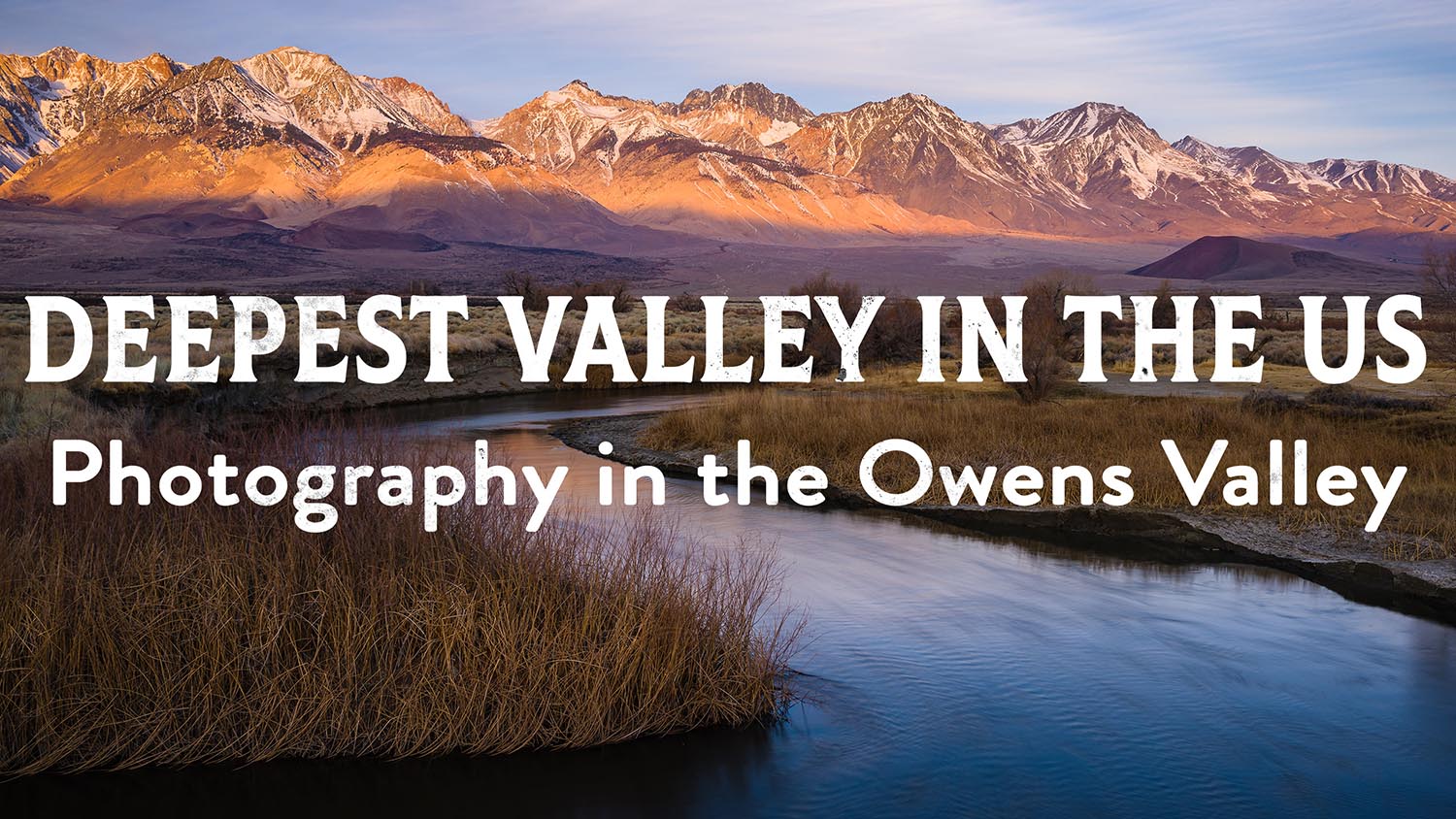

Earlier today I showed a friend of mine my most recent photo, taken at sunset at a place called Abalone Cove.

Now, my friend has been to this place before, and the first words out of his mouth were: “That’s not what it looks like.” In good fun, he also made some comments about me creating a “fake world” by blurring the water and the clouds. I gotta say, this irked me a little bit, but at the time I couldn’t think of how to respond to such a flat statement, so I didn’t say much of anything.

But his words weighed on me over the evening and made ponder exactly what I capture as a photographer. The knee-jerk idea that immediately comes to mind is that I strive to capture a moment in time, the “true feeling” of a given instant. But now I’m struggling with that statement because I think it’s hard to define exactly what it means. Delving slightly into the semantics of it, I’m first forced to wonder exactly what an “instant” really is and how the idea of an instant relates to what a camera is actually capable of capturing.

Looking at the technical side of things, what happens when you press the shutter button on a camera is that a sensor (I shoot digital) records all the photons that hit it as long as the shutter is open. So lets say that I’m shooting hummingbirds and I want to freeze the motion of a bird’s wings in midair; I’m going to set my camera up to have as quick of a shutter speed as possible, hopefully something in the 1/4000 sec range. That means the camera’s sensor is going to record all the photons that hit it during a length of time which is equal to 1/4000 sec: a fraction of a second, in all meanings of the term. Now let’s say I’m planning on shooting a meadow on a bright but cloudy day; I’m going to stop down my aperture for maximum depth of field with the result that my shutter speed might slow down to somewhere in the neighborhood of 1/100 sec; still a fraction of a second by most people’s reckoning. Both of these shots capture what is arguably an instant’s worth of time, and yet the second shot was 40 times slower than the first! In the time span of the second shot, I could theoretically have captured 40 images of the hummingbird. Does that mean the second shot wasn’t a single instant, but rather 40 instants strung together? In my mind, it’s still a single instant, because what is the difference between the two? In both cases, the sensor is recording photons for a given length of time; the second just happens to be arbitrarily longer than the first.

But hold on then; what if we draw this out farther along the same logical lines? If a factor of 40 increase in shutter speed doesn’t destroy the meaning of an instant, what about another 50-fold increase? Now we’re at a shutter speed of 1/2 sec. Are we starting to lose the meaning of the word instant? Starting to get a little hazier, methinks. What if we go out another 500 times to an exposure of just over four minutes? I think most people would agree that four minutes is hardly “an instant,” but where does the dividing line go up between “instant” and “non-instant”? When I look at things like this, I’m forced to say that I can’t arbitrarily create a point where shutter speeds faster than X capture an instant, and shutter speeds slower than X don’t capture an instant.

Which means I have to look elsewhere for the definition of the word “instant” as it relates to photography, and especially to my field landscape photography. The obvious thing which comes to my mind is feeling. Throughout the day, the feeling, tones, and mood of any given scene change due to variations of the light illuminating that scene. And that’s really what any photographer is trying capture (whether he knows it or not): the feeling of a certain place while he was there in person, experiencing it. So doesn’t that really help us define what an instant is? Let me give it a shot: an instant is a duration, during which the feelings, mood, and emotions of a scene don’t change. Whether that be 1/4000 sec or 4 mins, each shutter speed is designed to capture the individual feeling of that specific length of time, that instant. If the feel of a place doesn’t change over a period of time, who cares if that time is short or long? I’m forced to the conclusion that both can be “instants.”

Something else my friend’s comment made me think of is the purpose of art. I’m sure I could wax philosophically about that subject for posts on end, but I’ll sum up my views on the subject as briefly as I can. In my opinion, the point of art is to show us the world around ourselves, but not just in a way that we recognize it as the world. Art should peel back the layers so that we see or feel something new about the world. We should walk away from a piece of art slightly different people than we were when we walked toward it, having learned something, or seen some hidden truth about the world.

And I feel that in that respect, landscape photography is no different from any other art. Granted that landscape photography is in general a very true-to-life kind of art, but that doesn’t mean that it should mimic the real world as closely as possible. If that were the case, the robotic camera on top of the Google StreetView car would be creating masterpieces every day. But it isn’t, and that’s because art requires an artist to make creative decisions about how to interpret the world in a way that brings something new to the table, even if that something new is simply the beauty and wonder of a given place.

For the photo above, it wasn’t taken by a robot whose job was to obtain an image which mirrored real life as closely as possible. It was taken by me after I made specific creative decisions about how to interpret the beauty and emotion of Abalone Cove. And to be completely honest, this final image doesn’t bear a remarkable resemblance to any frozen moment in time at the cove that evening. If that were the case, I should have captured a massive wave crashing on the rocks in front of me and sending spray high into the air. And while a photo like that might better have conveyed the drama of the sea that night, it wouldn’t get across the point that I wanted to make about the motion of the sea and the clouds, the swirling whites of the water, the almost-surrealism of the constant swells and gushes of water on the rocks. And in truth, I also really wanted to see what would come out after a very long exposure. But regardless of the actual choices I made and the reasons behind them, my point remains the same: I interpreted this place and its emotions and made the artistic choices I felt necessary to convey those feelings in an image.

Taking this back to my friend, now I know I’ve got a much better reply if he ever says “that’s not how it looks” to me again: Am I simply trying to capture how a place looks at a moment frozen in time? Absolutely not, because the wonder and beauty and feeling of a place is contained in so much more than just the way it looks. Rather I’m trying to capture how a place feels in the instant that it feels that way, to capture my emotions in a way that relates to the beauty of the scene, and to use my camera as an interpretive tool to convey those feelings to a greater audience. I think that rather than create “fake worlds,” as my friend suggested, I’m really trying to reveal the hidden truths.

share this article: